Fulbright RESEARCH

Re-Defining Native: Re-tracing the Origins of the Amazonian Parrots of California - Supported in part by the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies at Harvard University and by the Fulbright Foundation

(Countries: Brazil and Mexico)

International Sponsorships:

Felipe Milanez, PhD, Political Ecologist, World-Renowned Documentarian, UN-Dubbed "Forest Hero," Professor at the Federal University of Recôncavo da Bahia

Dr. César A Domínguez Pérez-Tejada, Director of the Institute of Ecology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico

US Advisors:

Neil Brenner, PhD, Professor of Urban Theory, Director of the Urban Theory Lab, MDes-Urbanism, Landscape and Ecology Concentration Co-Coordinator | Harvard University - Graduate School of Design

Bradley Cantrell, Associate Professor of Landscape Architectural Technology, Program Director of the Landscape Architecture Program, MDes-Technology Concentration Co-Coordinator, Responsive Environments and Artifacts Lab | Harvard University - Graduate School of Design

Erle Ellis, PhD, Professor of Geography and Environmental Systems | University of Maryland, Baltimore County, Visiting Professor of Landscape Architecture | Harvard University - Graduate School of Design

--

Additional Advisors: (This research was initially developed within Harvard University's 2013-2014 academic courses: ADV-9661: Proseminar in Urbanism, Landscape and Ecology; ADV-9644: Research Methods in Landscape Architecture; and SES-5345: Critical and Social Cartography)

Charles Waldheim, John E. Irving Professor of Landscape Architecture | Harvard University - Graduate School of Design

Matthew Wilson, PhD, Associate Professor of Geography | University of Kentucky, Visiting Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture, Urban Planning and Design | Harvard University - Graduate School of Design

Ed Eigen, PhD, Associate Professor of Architecture and Landscape Architecture | Harvard University - Graduate School of Design

Cite as: Estrada, Leif. (2016). Re-Defining Native: Re-tracing the Origins of the Amazonian Parrots of California. Washington D.C.: Fulbright Foundation. Research.

PROPOSAL:

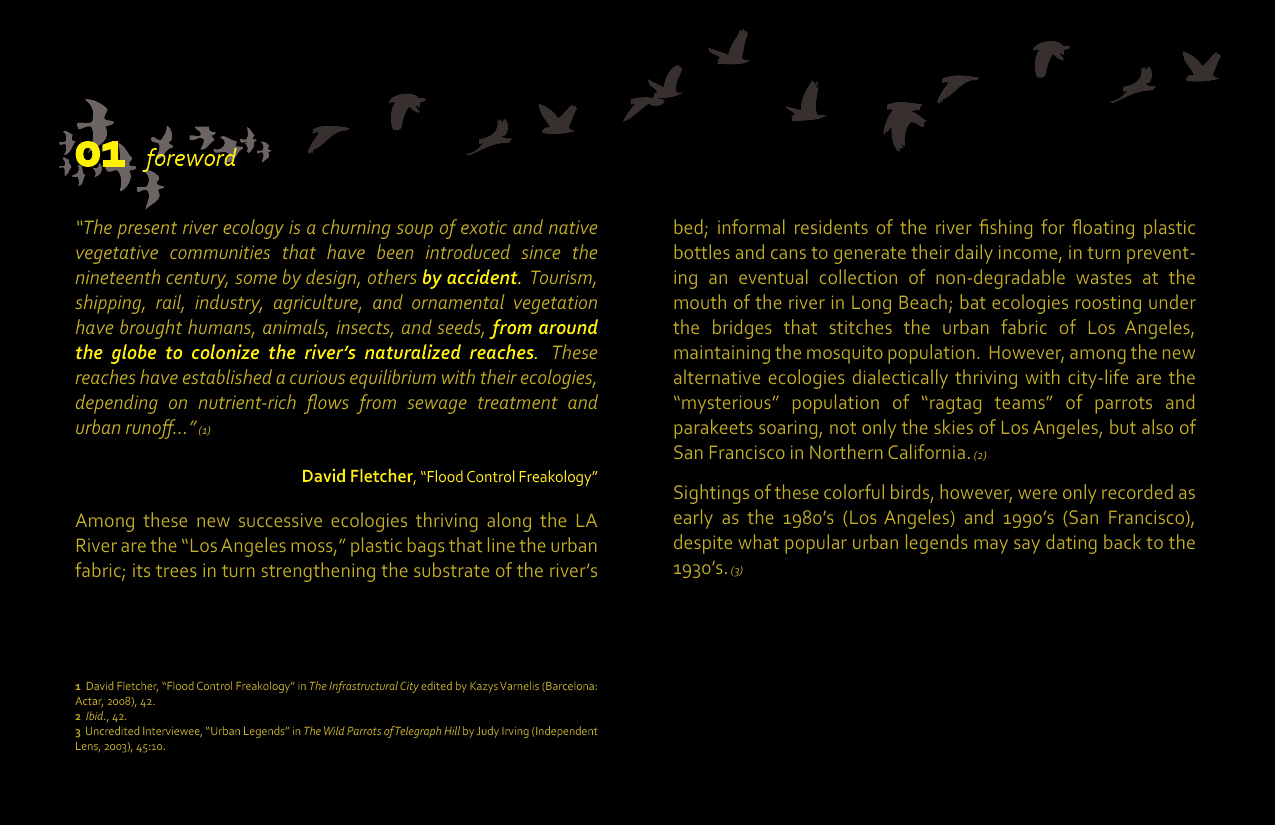

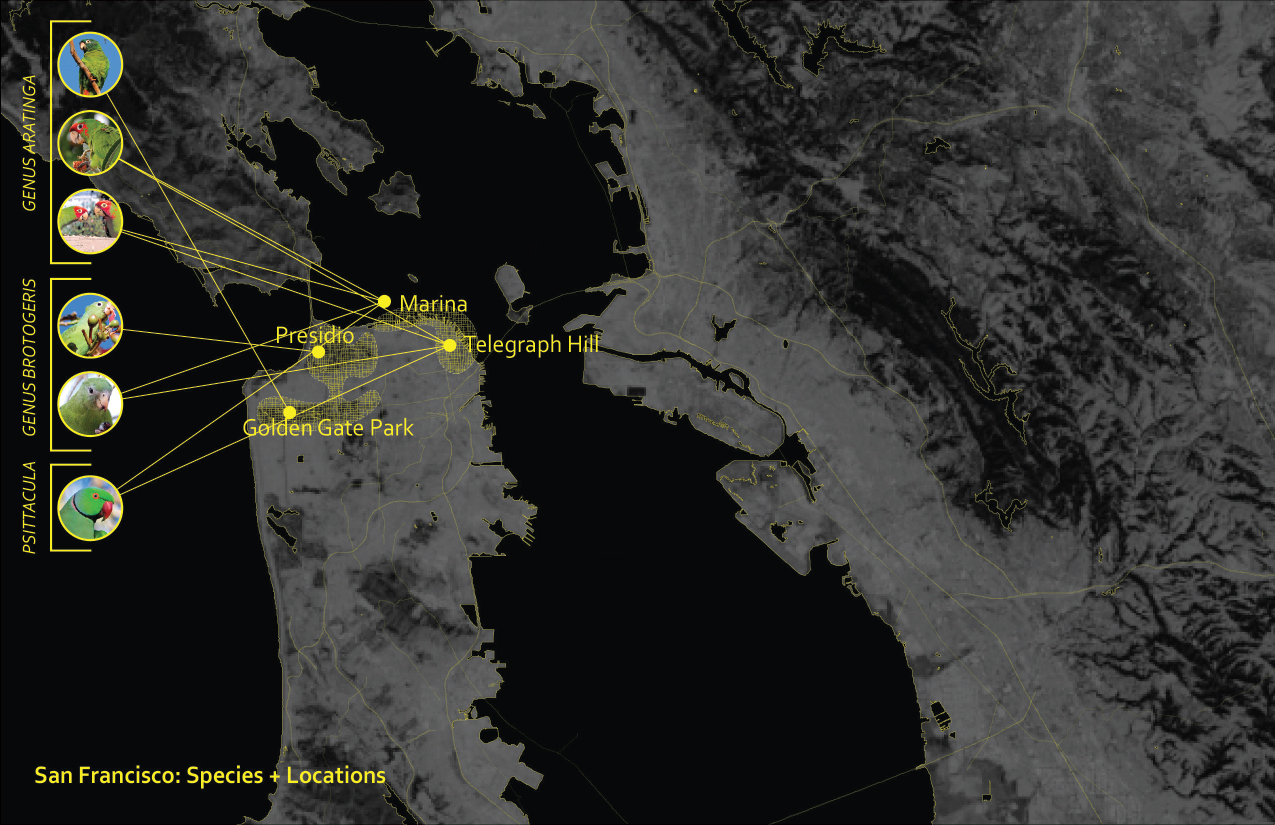

The only known “native” parakeet in the US became extinct in 1918[1], which can be found as mounted taxidermies in many natural history museums around the world, including Harvard’s. Today, however, flocks of parrots and parakeets can be seen across the skies of many American cities. An estimate of more than a dozen species have “naturalized” in Los Angeles County, alone. How they arrived in the country remains a mystery, with many urban legends purporting their arrival from the jungles of the Amazon.

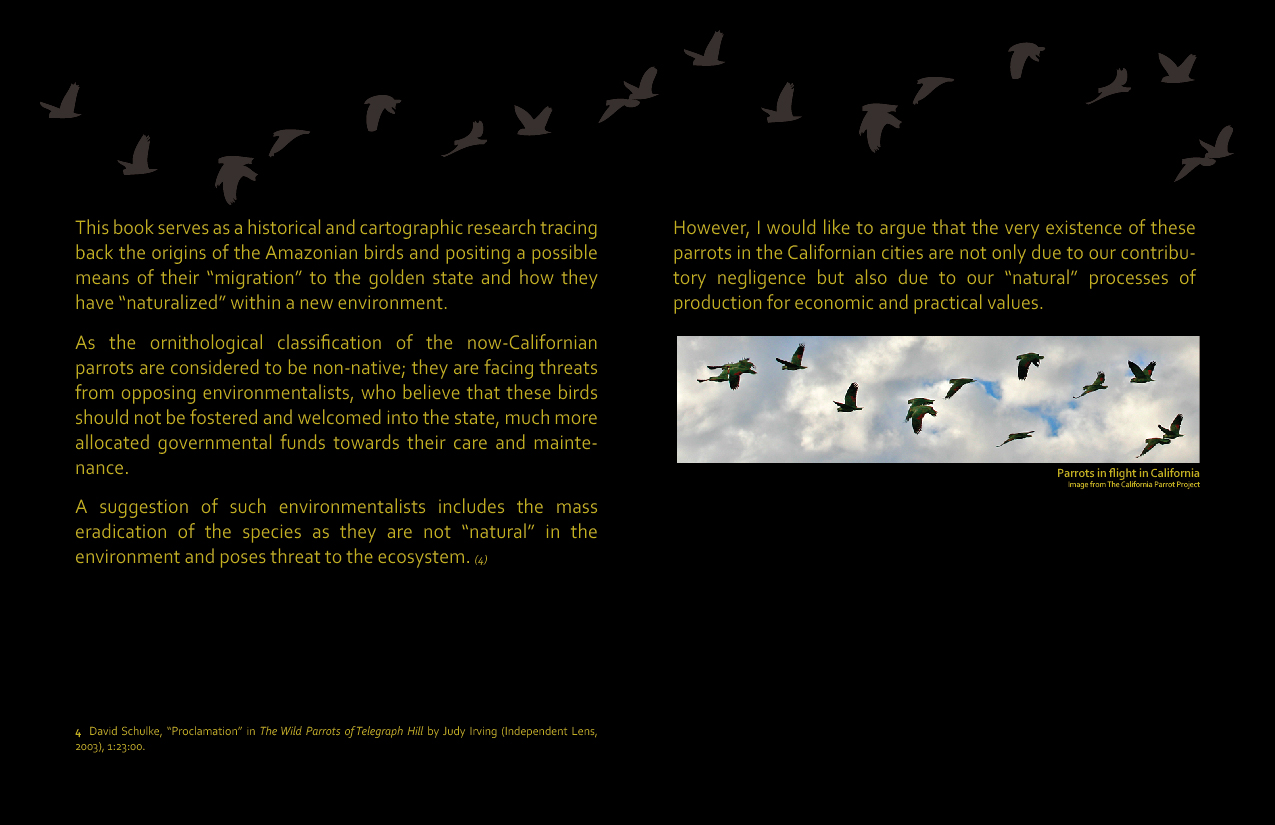

My Fulbright proposal, within the scope of the Critical Species theme, aims to retrace the origins of the Amazonian parrots and parakeets and reveal the latent benefits these avian species have provided historically to the locales it “naturalized” in, which have been forgotten as they are now seen as a nuisance or “invasive” to the urban ecosystem. Producing 3 cartographic video documentaries, I will retrace the birds’ “unnatural migration” from the Amazon, to the breeding grounds in Mazatlán in Mexico, by re-telling their forgotten stories and those that enabled their displacement 4,000 miles north of their origins. I am also intending to utilize this as a case study in the expansion of my graduate thesis in the study of what constitutes as “natural” and “native.”

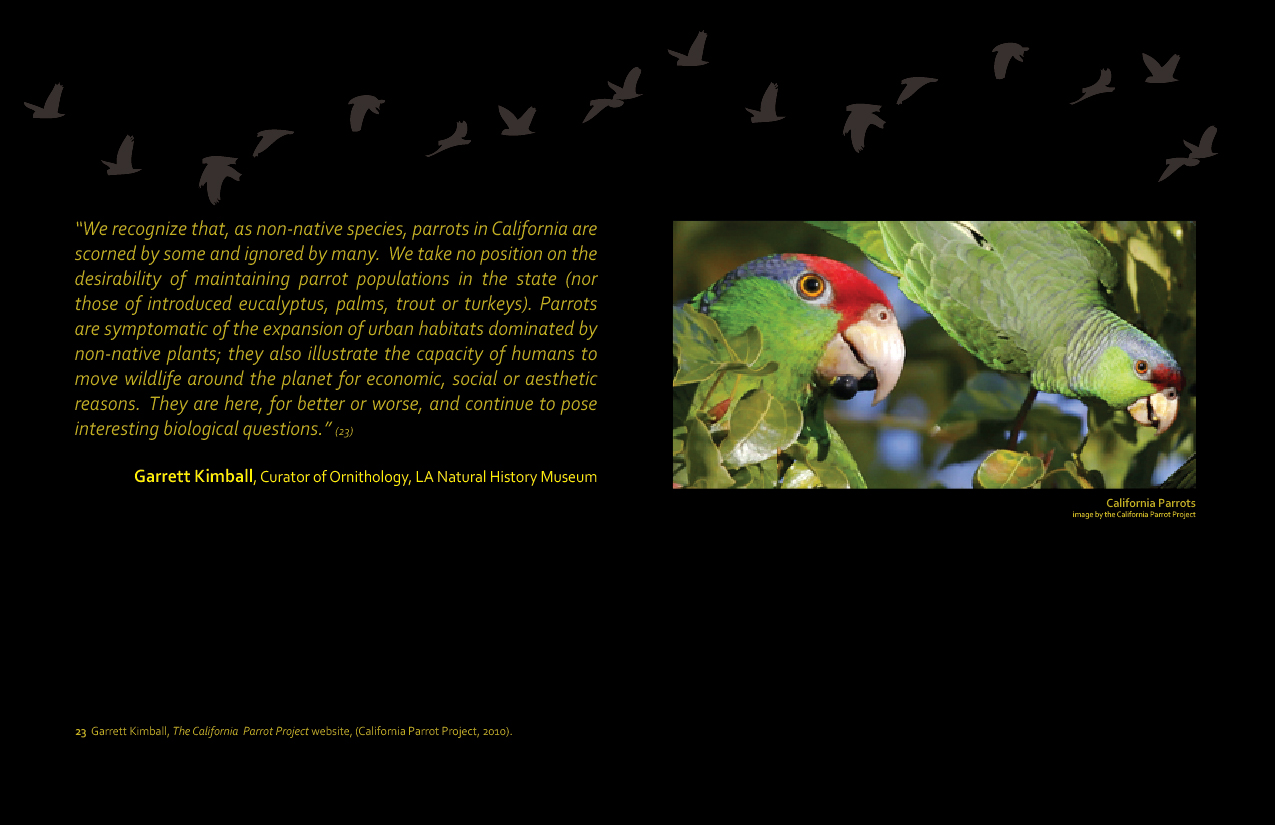

While many scorn and oppose the “non-native” species, due to institutionalized definitions of “invasive,”[2] it is important to understand that these birds are symptomatic of our productive processes of urbanization. They are byproducts of our capacity to move wildlife across the world for economic gains. They are here because of us, and they are here to stay as we continue production.

Theoretical Framework and Project Background

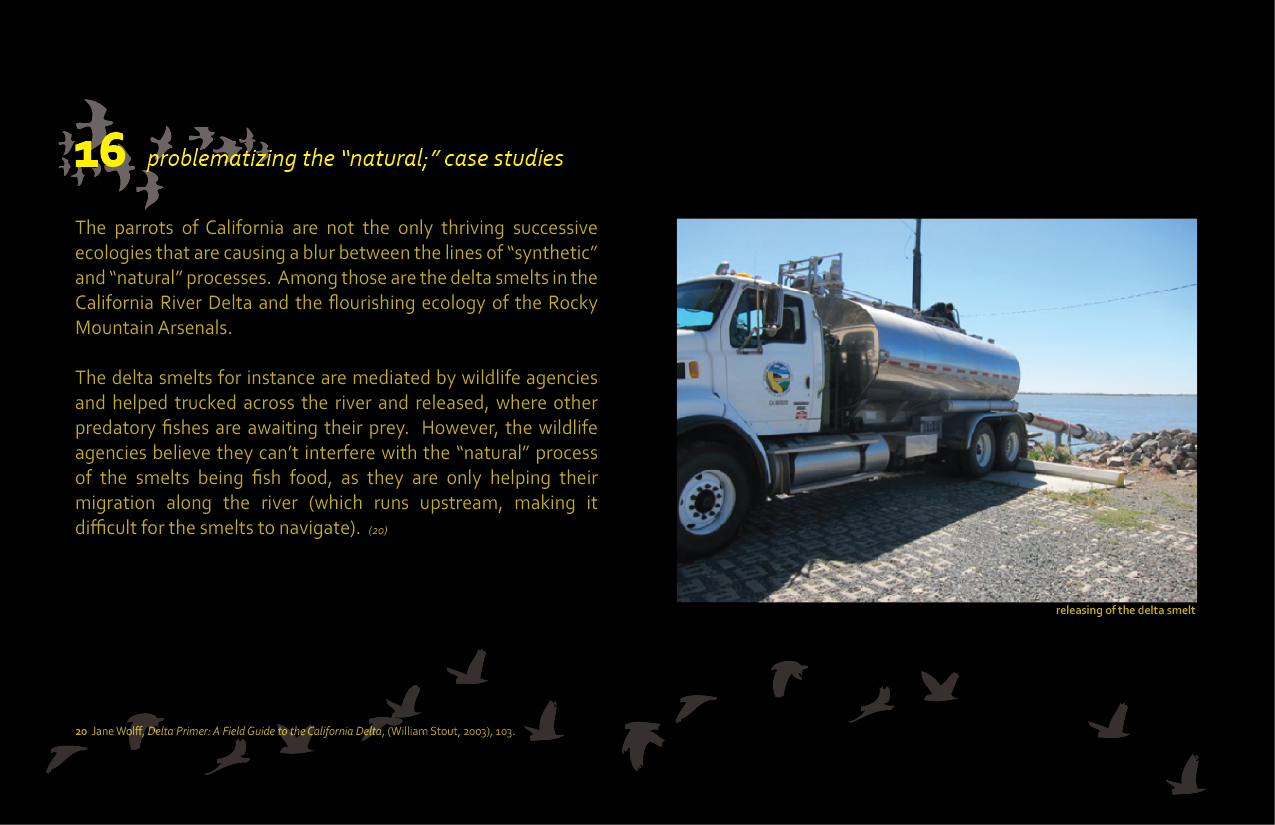

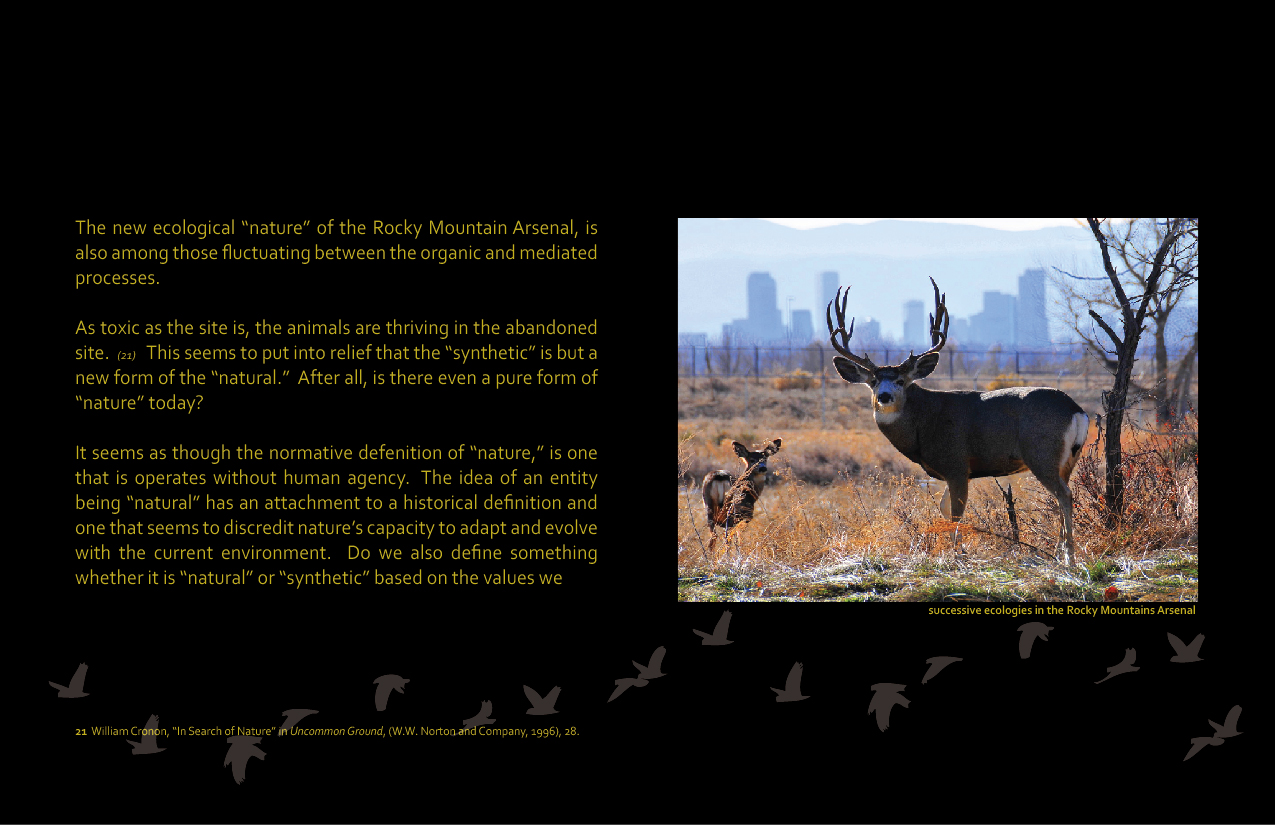

My research stems from the accepted norm that our environment is degrading and the perceived notion that Nature is in danger is problematizing the value of emerging successive ecologies. This notion even oversimplified the complex processes of Nature itself. Ubiquitous substances such as pollution are immediately deemed bad, without consideration that its “impurity” is an indication of a productive system. This creates a dichotomy between the “idealized and untouched” Edenic image of Nature and the so-called “negative effects” of production. This paradigm proliferates policy-making where novel ecologies that emerged as accidental forms of production are labeled as invasive, and are threatened by environmentalist groups who support a restoration of Nature to an arbitrary ideal point in time.

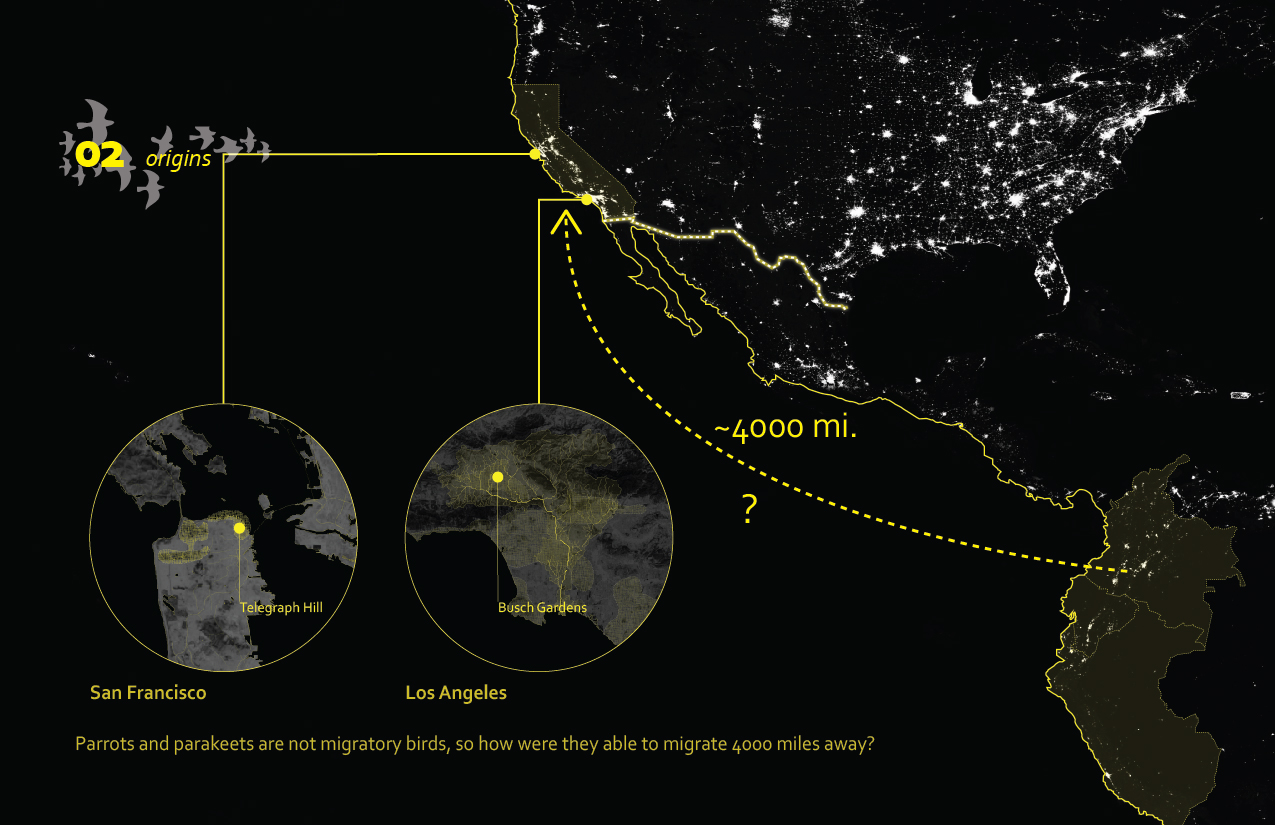

The population of ragtag teams of parrot and parakeet species that mysteriously arrived in LA decades ago is facing scrutiny for their “non-nativeness.” Their unknown benefits, of practical and cultural value to the urban ecosystem, pose a threat to their very existence as they are classified as ‘non-native.’ Many environmentalists believe that these birds should not be fostered and welcomed into the state, much less governmental funds be allocated to their care, protection, and in-depth ecological study. Environmentalist groups even suggested the mass eradication of the species as they are not “natural” in the environment and pose threats to the ecosystem.

To know the historical origin of these birds is important to understand, as their existence as “alternative” and novel ecologies hinges on our processes of production and urbanization. As byproducts of Capital production, we must realize that they should not be blamed for the changing ecology or be seen as “consequences” due to our contributory negligence; rather these avian species must be accepted as part of the complex, evolving processes of Nature itself.

Historical Site Background + Political Framework

In 1978, the Amazonian Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO) was established, which aimed to promote a sustainable development of the Amazon including the “management, monitoring and control of wild flora and fauna species endangered by trade.”[3] The policies created by this formation was fueled by historical accounts of resource extraction and exploitation (sp. of other nations) that have been happening in the territory since the late 19th century, similarly with the case of the Amazonian parrots.

Historically, these included the dispersal of the rubber tree across Southeast Asia and Africa by a British explorer, and Henry Ford’s pre-fabricated city of Fordlândia that secured the source of rubber for his company. Without a policy that regulated extraction, the Amazonian region’s extractive product was short-lived. Moreover, other nations mostly benefited from it.

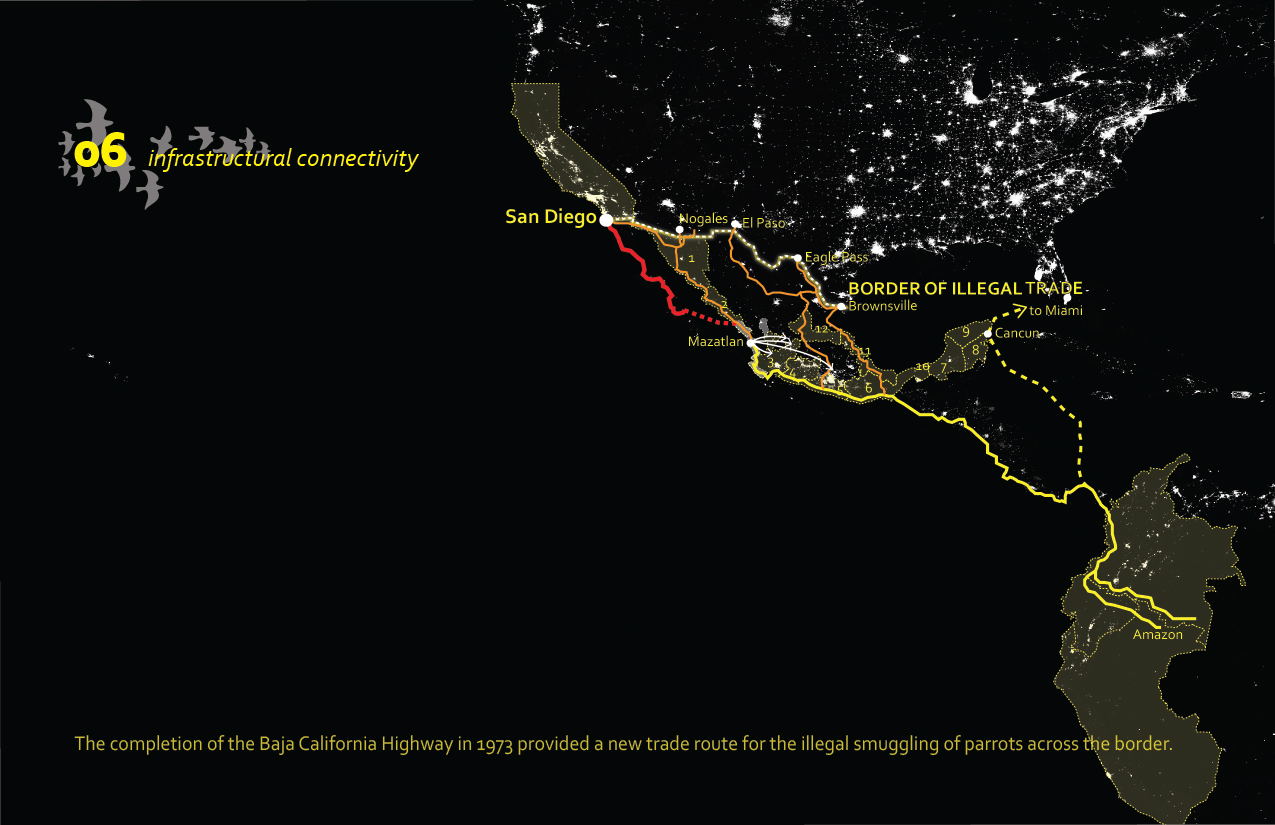

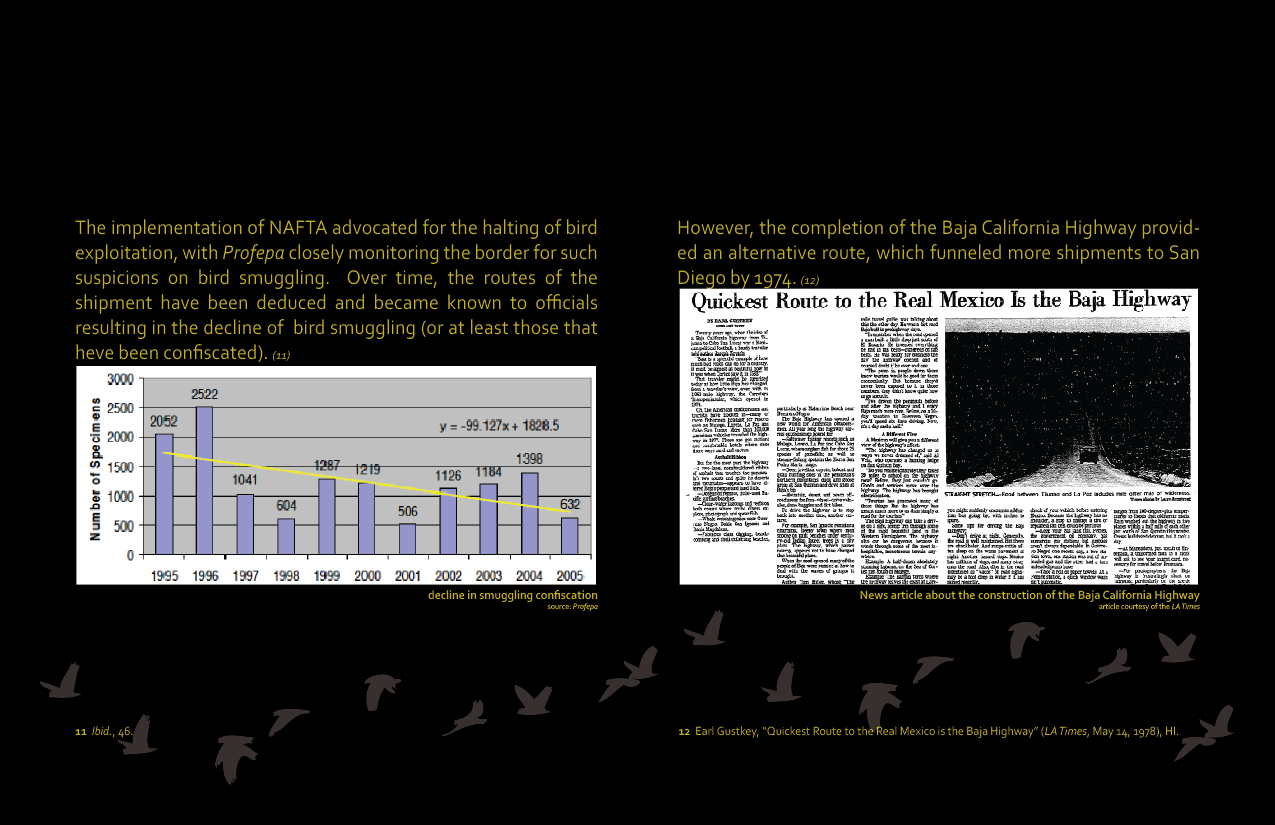

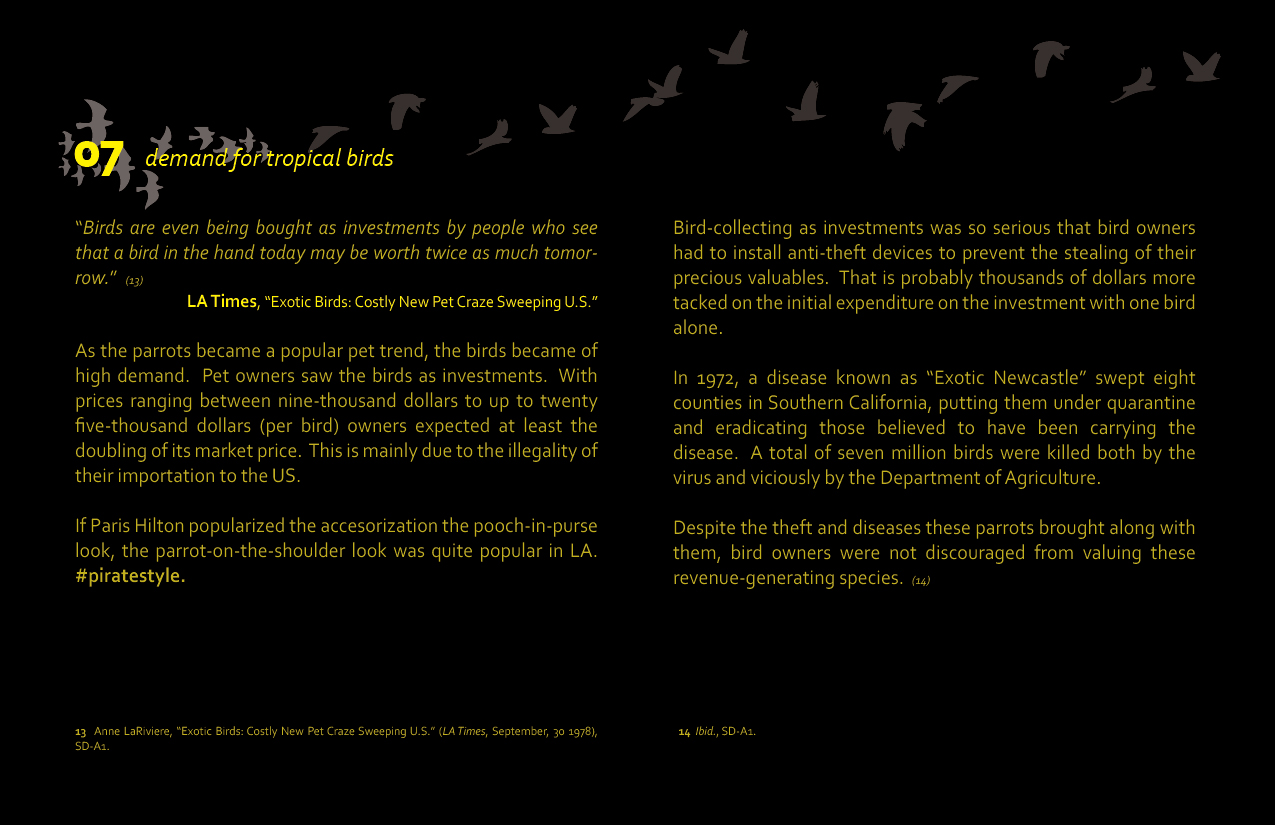

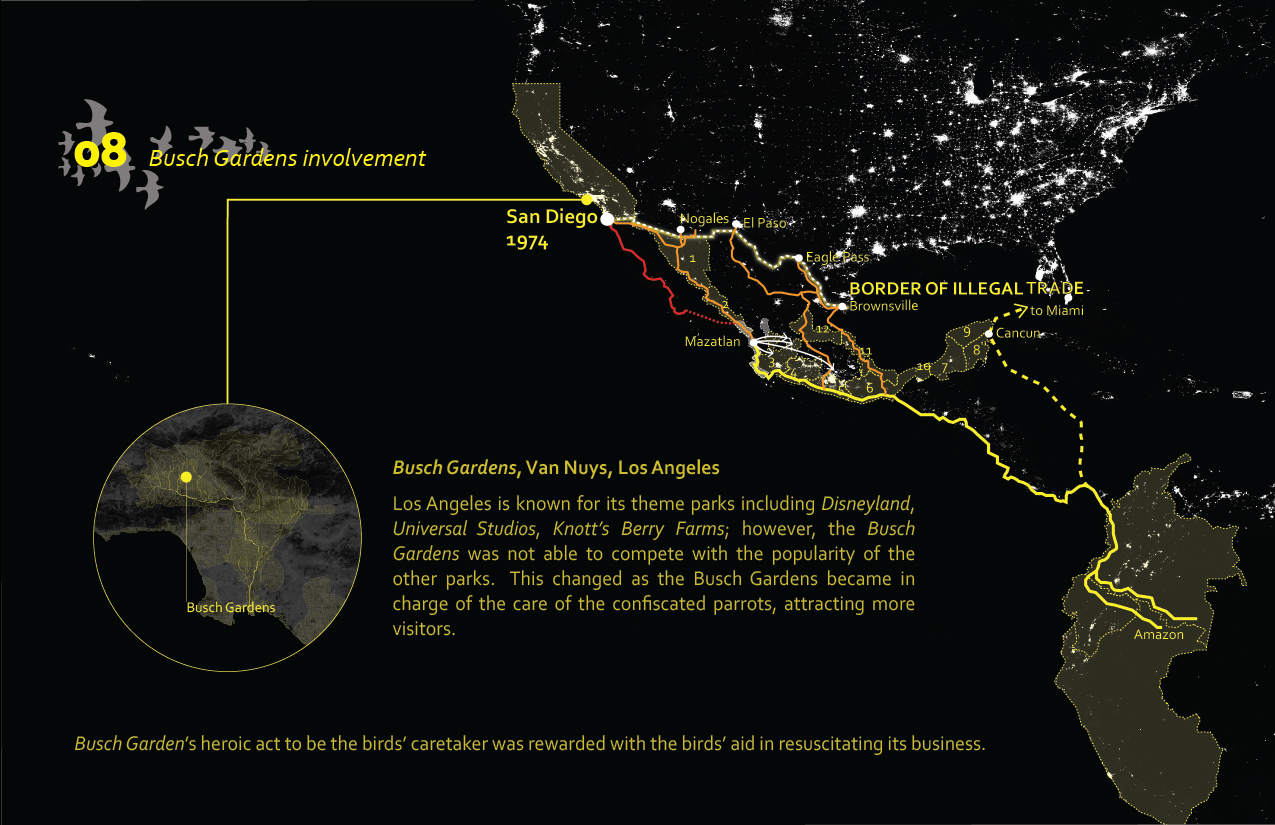

By 1992, the Federal Attorney for Environmental Protection (PROFEPA) was also created in Mexico to enforce the preservation of the environment along with monitoring the border for animal smuggling, which it aspired to halt.[4] However, this did not stop illegal extractors, as bird trade became a predominant economic generator that persists until today. Despite these enacted policies, the creation of infrastructural systems, such as the Baja California Highway, only facilitated the continued illegal bird trade.

Project Methodology + Site-Specific Stories

Through a series of historical and projective cartographic animations, documented on-site interviews, videos, and photography, I will produce 3 video documentaries narrating how these non-migratory birds “migrated” from Amazonian Brazil to Mexico and eventually to the US (focused on a specific theme per country: Extraction, Breeding and Naturalization). Each of the countries played an important role in the eventual arrival of the birds in the US, and the stories of their local people, larger governmental entities, and spatial and temporal contexts will be told through a 3-episode video documentary. Through the understanding of these phenomenological entities, I hope to provide a new alternative definition to what constitutes as “natural” and “native.”

In the winter of 2015, I will be visiting Brazil to conduct the initial onsite research and affiliation interview with the support of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies at Harvard University. With the use of humans and animal species as the subject of my research, my school’s Institutional Review Board reviewed that my project methodology is ethical.

Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil: Extraction

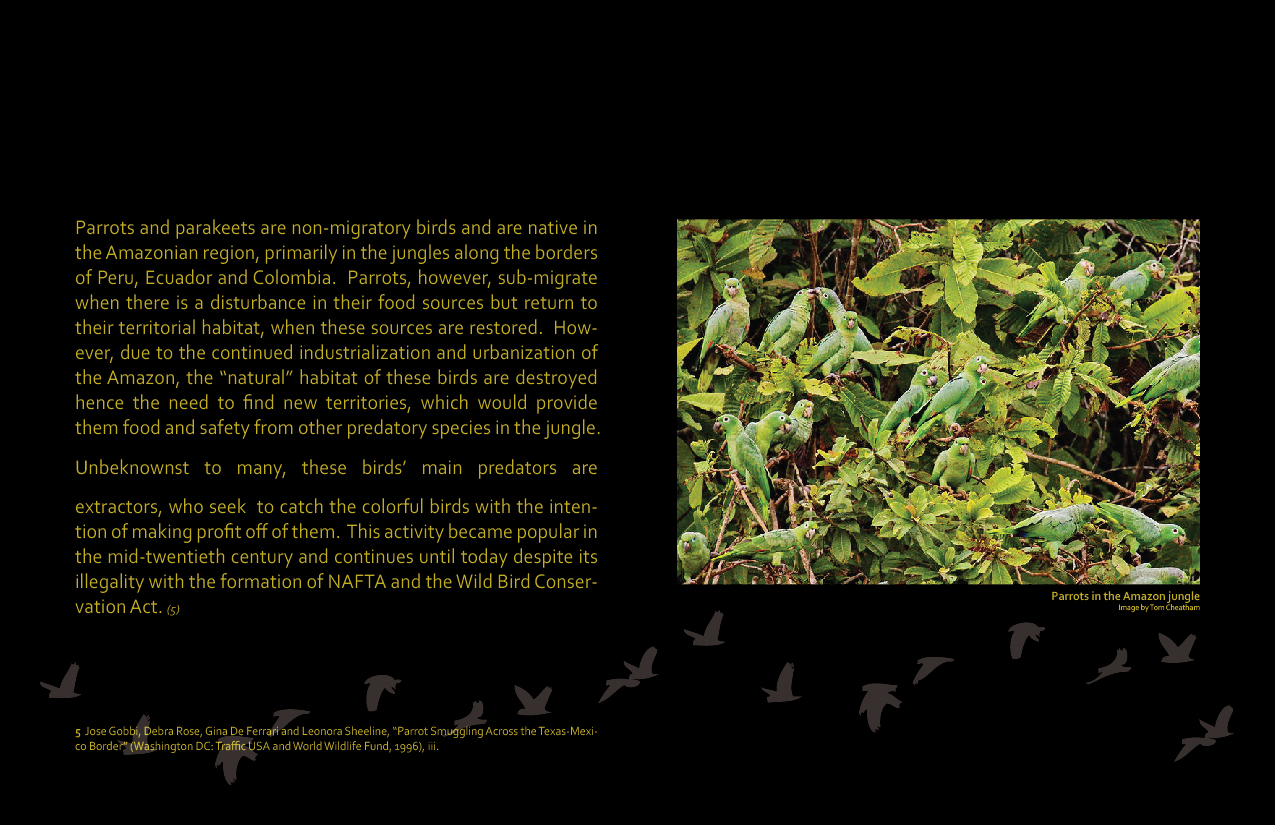

Manaus, being the capital of the province of the Amazonas, along with its Free Economic Zone would be an initial site of analysis. I will look at how the established economic zone influenced bird extraction, despite its already lenient taxation on trade. Who is behind the extraction of the bird species from the Amazon and what are the overall motivations behind this practice?

While in Brazil, with my conversational knowledge in Portuguese I will interview the people who were part of the extraction of parrot and parakeet species from the Amazon, learn about their stories about the capturing of the birds and how has this practice affected the current parrot ornithology and present ecology of the Amazon. Their local knowledge will be helpful in developing cartographic representations, which will be gathered through a series of participatory GIS meetings that I will conduct locally. Historic transition of bird occupation through the present will be produced as an animated cartography showing the effects of extraction.

While in Brazil, I will be advised by renowned UN-dubbed “Forest Hero,” Amazon environmentalist and documentarian, Felipe Milanez, who will be starting his professorship at the Federal University of Recôncavo in Bahia. His expertise and guidance in the region will enable me in engaging with the local communities, most specifically the indigenous tribes he featured in his documentaries for National Geographic, Discovery Channel and Vice. Professor Milanez also offered his technical expertise in documenting both still and video footages.

Mazatlán, Mexico: Breeding

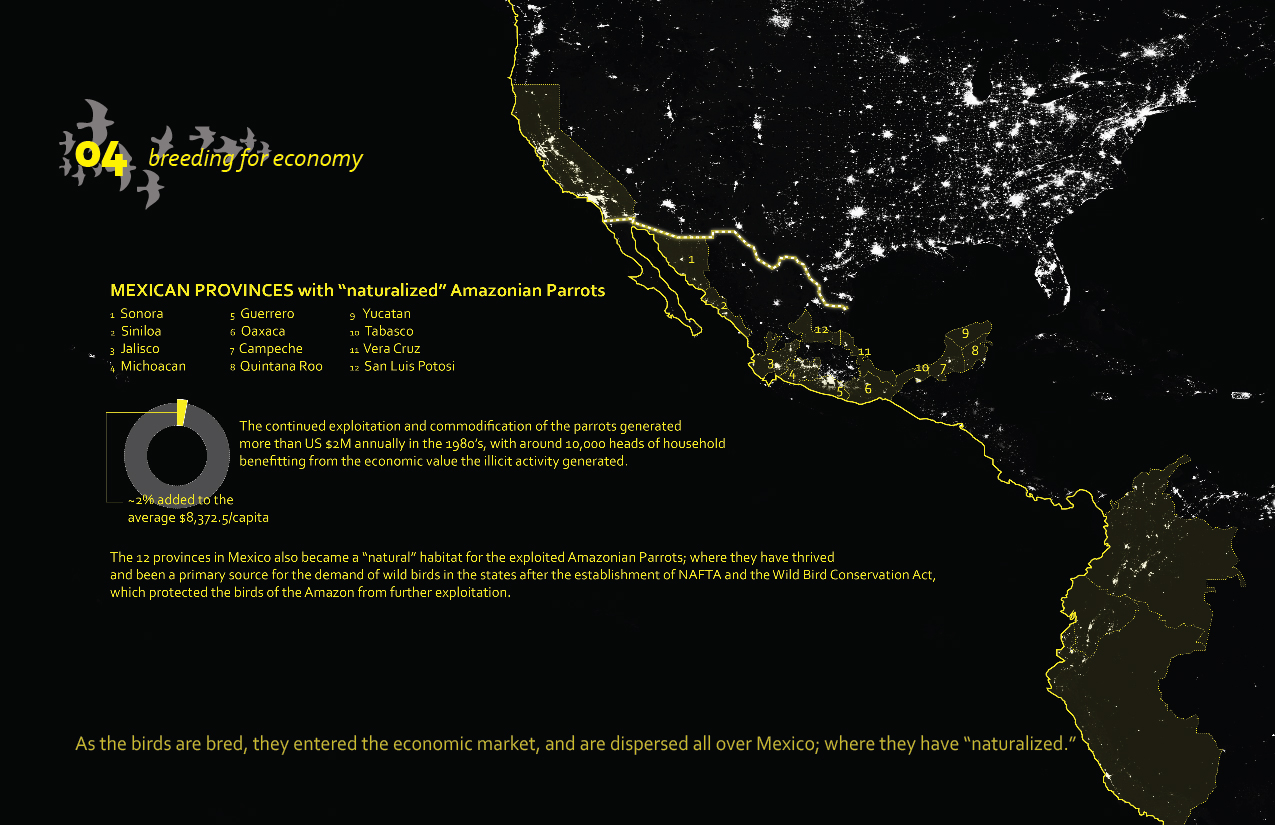

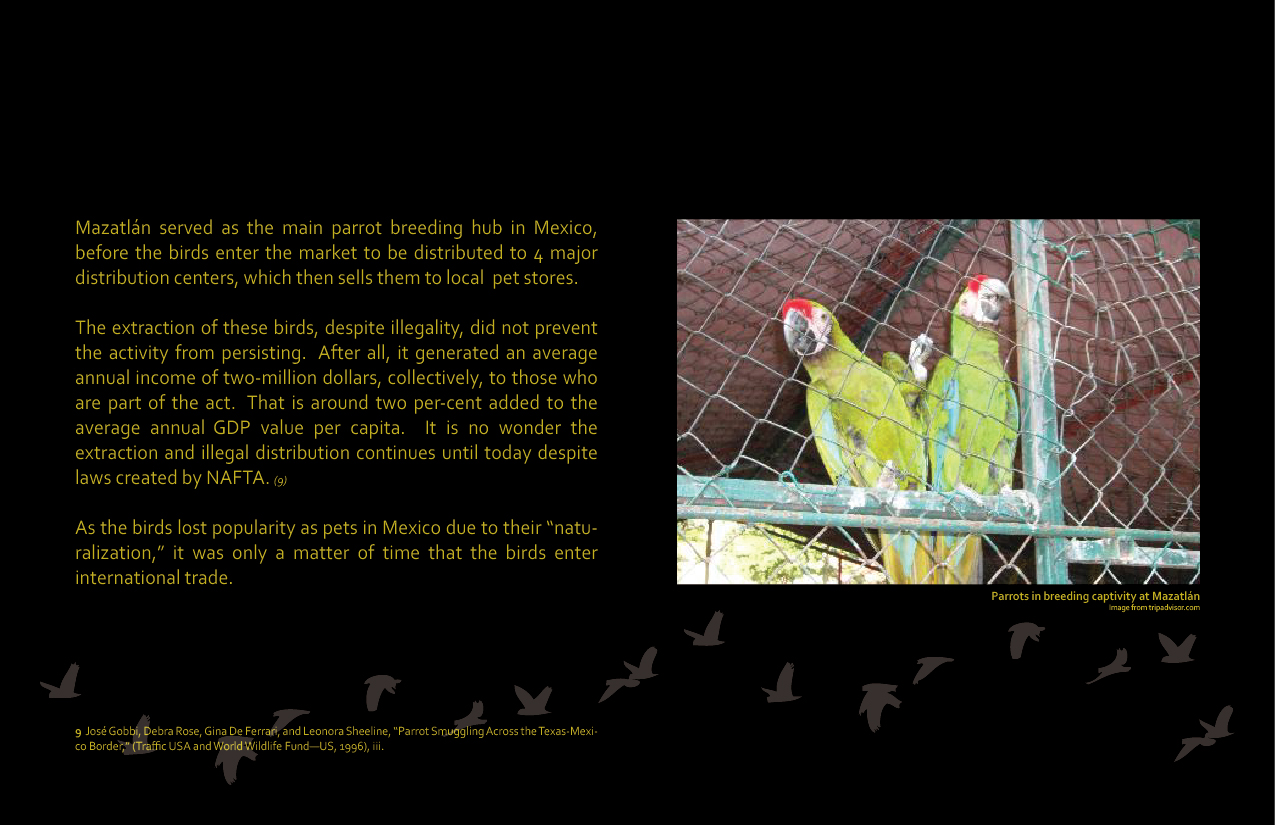

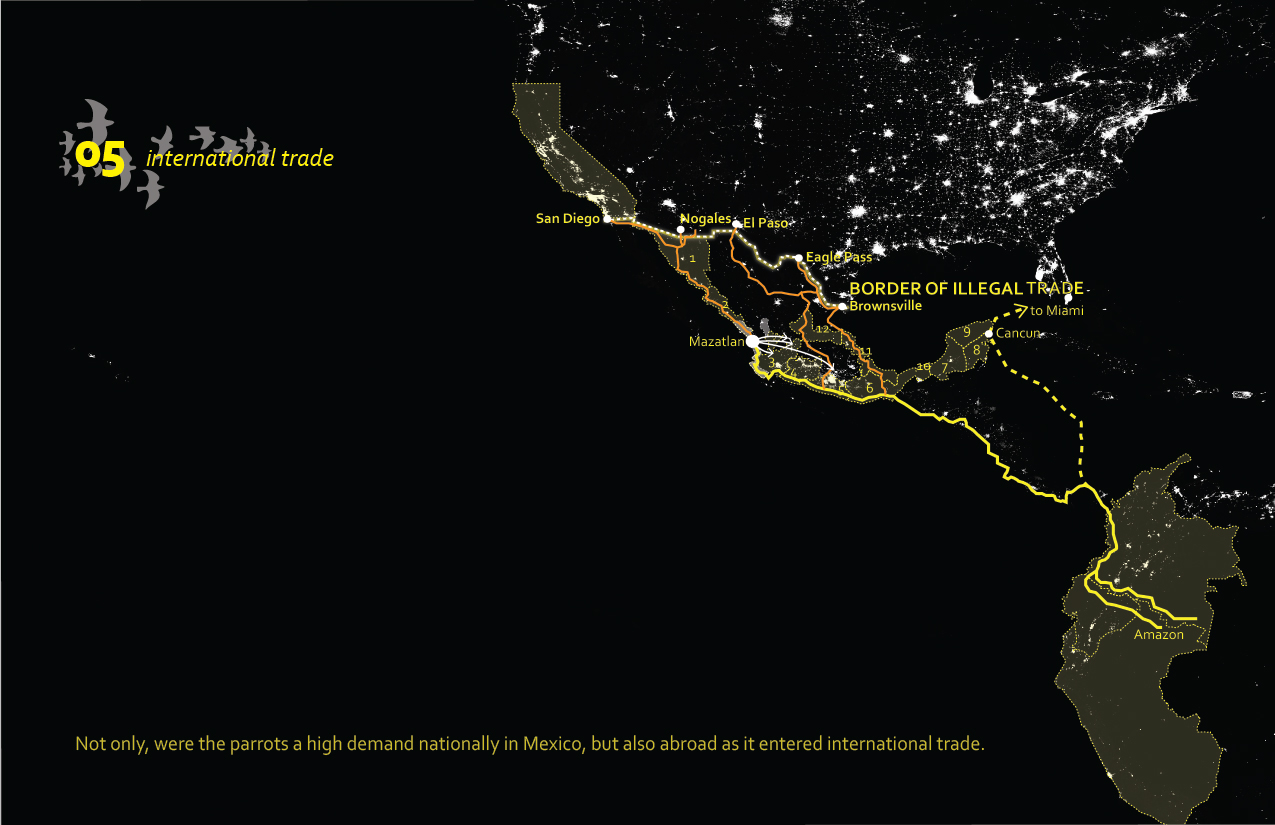

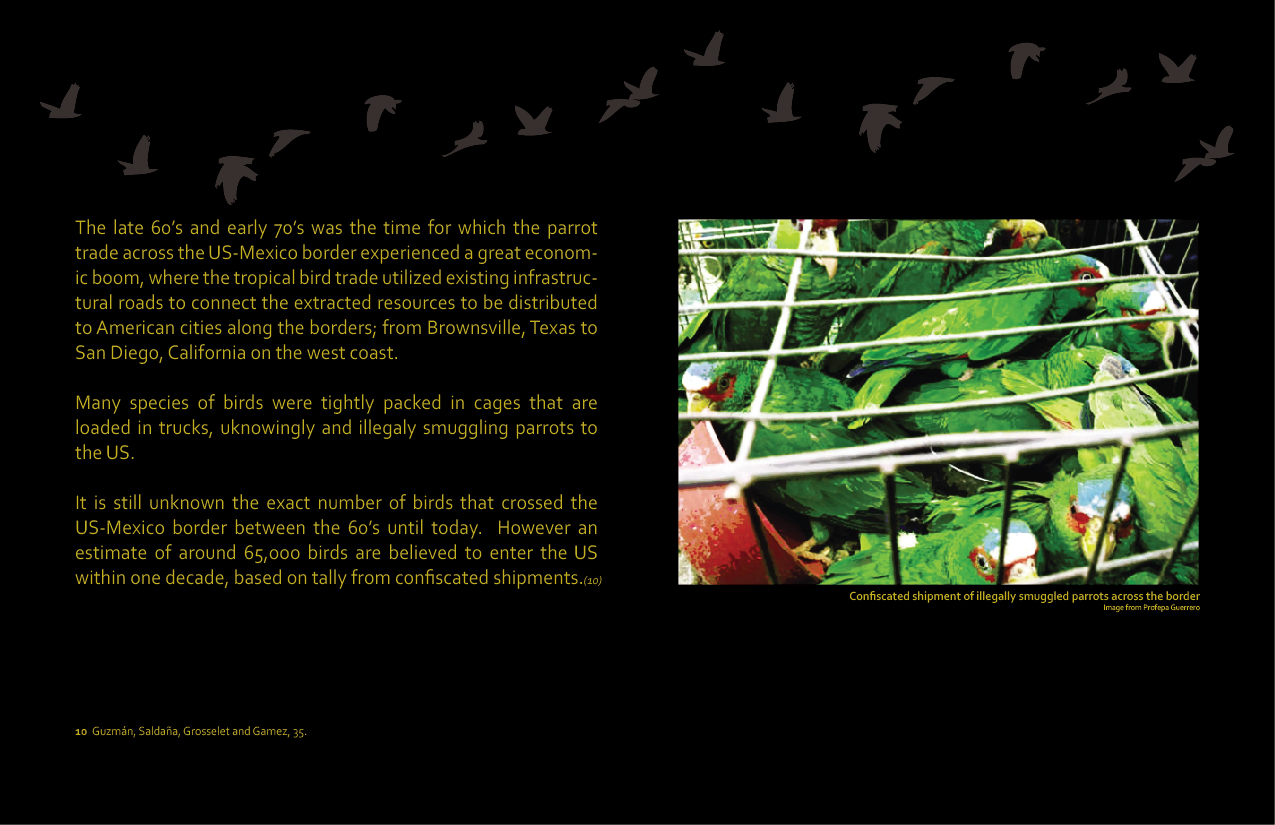

Serving as the breeding ground for the extracted Amazonian birds, Mazatlán became the epicenter of parrot and parakeet trade in Mexico before the birds were tightly packed in water bottles and small cages to be smuggled across the US-Mexico border. It is also the reason why the birds have “naturalized” in Mexico’s 12 provinces.

In the 1980’s, commodification of these birds generated an average of $2 Million annually with about 10,000 families benefiting from the illicit activity. My goal is to tell the stories of the families who economically benefited from the breeding and illegal smuggling of the birds across the border. Through these first-hand interactions, with the assistance of my sponsoring institution in Mexico and my advanced knowledge of Spanish, I will tell their story through one-on-one interviews of historical accounts of the activity.

The Ecology Department at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) will be serving as my sponsor in Mexico. The Director of the Ecology Department, Dr. César Domínguez Perez-Tejada along with urban ecologist and ornithologist, Dr. Iriana Zuria has agreed to supervise my research and provide any resources I would need in successfully delivering the research and project.

Synthesis: Naturalization

In the end, the third video will synthesize the entirety of the story of the parrots and parakeets’ journey from the Amazon, to the breeding grounds in Mexico, and focus on their eventual entrance into the US. Along with it is my goal to provide an alternative understanding in the classification of what is “natural” and “native.” As an advocate for the now-Angeleno parrots and parakeets, I intend to continue on this research upon my return to the U.S. with the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and its Ornithology Collections Manager, Garrett Kimball, who has already provided support in the initial development of my research.

Footnotes:

[1] The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, “Conuropsis Carolinensis,” Available from: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/22685776/0.

[2] California Invasive Species Advisory Committee, The California Invasive Species List, (Sacramento: Invasive Species Council of California, 2010), p. 9.

[3] Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization, Amazon Strategic Cooperation Agenda, (Brasilia: Organização de Tratado de Cooperação Amazônica, 2010), p. 26.

[4] Federal Attorney for Environmental Protection, Article 60 Bis 2 General Wildlife Act, (Mexico DF: Procuraduría Federal de Protección Al Ambiente, 2014).

PERSONAL STATEMENT

Similarly to the “naturalized” parrots of California, I too have lived in many places, making it a personal challenge to answer a simple, yet politicized, question of “where are you from?” Born in the Philippines, I immigrated to Maui,Hawaii at the age of 11 during a political turmoil that impeached the country’s corrupt president, who unfortunately was a distant family. Maui became a sanctuary where my family was able to escape people’s judgment, even though we did not belong to the incumbent’s political party and was actually even in support of the shift of political regime. After highschool I attended architecture school in San Francisco. Until today, I cite those three places as “where I’m from,” as I feel culturally attached to Maui and San Francisco even though not identifying as a “native.” However, it is a struggle to relate back to where I was born, as it has been more than 10 years since my last visit.

Pursuing graduate degrees in Landscape Architecture and Design Studies, concentrating on urbanism, landscape and ecology, stems from living on an island, where “nature’s beauty” serves as the state’s economic generator through tourism. This preservation of Nature was something that was instilled in the local culture, where state laws constantly challenge, and sometimes hinder, development.

From a moratorium on a ferry system to connect the islands, to an arbitrary data-collection gathered from entering visitors (preventing entrance of unwanted agricultural products), Hawaii strives to create an image of Nature that is “untouched.” However, I always thought that the very subjection of Nature to such social constructs does not create a more “natural” Nature. If anything, it creates something that is no different than the “man-made.”

It is also very interesting that when new species begin to thrive on the islands, they are immediately demonized for their “exoticism.” Adjusting to life on Maui, felt the same. People had already formulated their opinions about myself because of my surname.

Our preconceived notion of what ‘Nature is’ is dangerous for what Nature could be. We reduce it so simply to subjective ideas, that we have no real understanding of it, and in many cases prevent its natural evolution.

My studies in architecture and the built environment put the dichotomous idea of production and the preservation of Nature head-to-head. As a designer, it is something that I continue to understand. Being in the field responsible for urban development, which causes for the continued transformation of the environment, I have always been interested in learning of new ways to design responsibly and ethically.

As we entered the epoch of the Anthropocene, I feel that designers must take on the larger responsibility of understanding the environmental and ecological impacts of design and spatial production. As designers, we can also be advocates that not only consider the aesthetic application to present spatial conditions, but also anticipating the projective environmental impacts of our built designs and how to responsibly mitigate such effects.

Upon completion of my research and studies, I intend to utilize the international experience I would acquire from the Fulbright Fellowship to inform my design practice—to strive in the creation of designs that actively consider the environment and taking responsibility for the novel ecologies that may emerge from the indeterminate ecological effects of spatial production. I will also continue my ornithology research with the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and contribute to the growing body of knowledge of the Amazonian parrots in LA.

Visual and Cartographic Narrative: